This review focuses on Zweig's comments on Jewishness and antisemitism, and two of the key thinkers he writes about, founder of Zionism, Theodor Herzl and founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, rather than attempting to cover the whole book "The World of Yesterday". By way of background, Zweig is briefly compared with Canetti.

Elias Canetti despised Stefan Zweig. They knew one another, of course. Zweig had helped Canetti publish his famous novel. Naturally the Nobel prizewinner respected his fellow giants of German language literature, such as Thomas Mann and Musil. But not a scribbler.

Both grew up in Vienna. Both were very international in outlook. Canetti, and the Sephardi family he came from, were polyglots and lived in various European countries partly by choice and partly by necessity. Zweig cast himself as a world citizen, really meaning a European, but was originally--and until the Nazis took away his passport, proudly--Austrian.

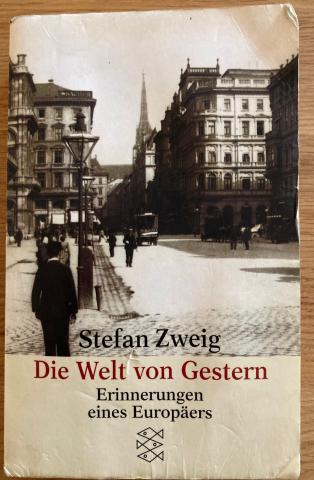

Canetti was an interesting intellectual, delighting in his sharp mind, who describes his interesting life and intellectual development in a finely crafted three-volume autobiography. Readers unfamiliar with Canetti except perhaps as Iris Murdoch's sadistic lover, might enjoy Professor Julian Preece's excellent article on him in The Guardian. Zweig, an immensely successful popular writer, starts his autobiography, The World of Yesterday, which I call his 500-page suicide note, by saying he had never been much interested in himself. So he offers nothing like Canetti in self-revelation. Instead he paints a flawed, raw, glowing and ultimately burning tableau of Europe c1890-1940.

The academic experts will quite rightly point out Zweig's literary infelicities and historical inaccuracies, and run back to Canetti, if he is currently fashionable in their world (which I doubt). One reads comments like "The writings of this once internationally popular..man of letters have fallen legitimately into obscurity..as his two biographers of a decade ago already realized". (Botstein, Leon. "Stefan Zweig and the Illusion of the Jewish European." Jewish Social Studies, vol. 44, no. 1, 1982, p. 63.) The general reader with an open mind and a beating heart will find Zweig reaches into their soul and changes their perspectives for ever.

For the English-speaking reader, Zweig's German, whilst not for the beginner, is not especially difficult, and arguably nothing special: it does a job efficiently, the job being to tell some stories and describe some people and places Zweig had known, and comment on them. One could read him in translation probably without missing much, which is on the whole not true of the "big names" of German, Austrian and Swiss literature.

Zweig took poison the day after sending the manuscript to his translator and agent, and towards the end of the book he indirectly tells us why, as I imply later.

In Zweig's approximately chronological patchwork of material he gives us segments of a few pages each on a range of themes; and portraits of a selection from the many famous people he knew. Because The World of Yesterday is not a "great book" it is possible, recommended even, to pick up a copy and use the index to select passages of interest, though it all repays reading if one has time.

The individuals to whom he most explicitly ascribes greatness reaching beyond their professional or artistic work are Herzl, and Freud. They frame Zweig's collection of portraits of great men. Theodor Herzl, the great man who started nineteen-year-old Zweig's career by giving him a break into journalism, is treated about a quarter of the way into the book, and Sigmund Freud, whom Zweig knew in his final exile, at the end. Zweig was impressed by the commanding and uncompromising personal demeanour of both men, characteristics which perhaps the charming Zweig himself lacked, though he himself did display something he admired in Freud: a pessimist about humanity but positive in his personal attitude, he was not one to hate and did not complain.

Of both, Zweig remarks how these men with world-changing vision--and whatever one thinks of them, their visions did change the world--offended contemporary Viennese Jewry, though for different reasons. The reasons for the offence were in the case of Herzl summed up in the comment of Jews who asked, "Why would we want to go to Palestine?" Jews from further east criticized him for not understanding Judaism. With Freud the offence was that, at a later time when Jews were seven-fold sensitive as a result of being shockingly treated, he suggested in Moses and Monotheism that Moses, the "greatest Jew", was actually Egyptian and not Jewish. This did not go down well.

Aside from the description of Herzl, Zweig does not say a great deal about Jewish questions. There is a famous passage in which he points out that whereas in the past the Austrian aristocracy had been great patrons of the arts and learning, by the late nineteenth century they had lost interest, and it was the newly enfranchised Jewish population who kept the theatres and newspapers and so on going. He adds that people thought Jews were keen on making money because many went into business, but their real motivation for seeking wealth was to make time for learning and the arts.

At the end of the book Zweig, leading on from his portrait of Freud, writes about Nazi antisemitism. He had written little about the background of racial unrest in pre-war Vienna. Earlier in the book he does describe Hitler's rise to power, the banning of his books, and of Richard Strauss operas for which he was librettist. He was one of the first to see the risks. Returning to the more evolved antisemitic policies of post-1938 at the end of the book, he seems to link the spread of hate with his own experience of statelessness, and with the less extreme but freedom- and time-robbing obstacles of modern travel: being fingerprinted like a criminal, having to show one's source of funds and prove one's vaccination status (yes, he mentions that!), for example. There was an implied connection between the greater horrors of Nazi persecution in its peculiarly twentieth-century flavour, and this recognition that in smaller ways humans are now treated by the state and its agents as objects, not subjects. He says that all started with WWI.

On antisemitism and what made it different in the twentieth century, he says that there was at least some explanation for past persecutions, dreadful as they were, in that the Jews kept themselves and their religion separate. The modern manifestation seemed all the more senseless since this was no longer the case. He also points out that what was likely new, in addition to the old murder, exile and expropriation, was the pleasure some of the persecutors took in random individual acts of brutal humiliation of Jews, behaviour which the civic authorities tolerated. There were of course humiliating laws too. Zweig's mother of 82 liked to go for walks in Vienna but she needed a sit-down after 10 minutes. The law forbidding Jews, even a woman of 82, to sit on park benches made her beloved walks difficult.

The portrait of Freud is significant because Zweig calls him "the best of us". He mentioned Freud several times, but knew him mostly in London, and that as well as Freud's importance, explains why Freud's is the last of the portraits in the book. Zweig showed little awareness of psychoanalysis, and certainly did not want his own sexual secrets explored (one German scholar has published a book arguing Zweig was a flasher). And yet with the praise he lavishes on Freud, one feels that Zweig intuited that Freud's work really mattered, really underpinned the explosive modernism which developed in the star-studded firmament of Viennese culture, and from which the journalist, popular historian and storyteller Zweig emerged. Zweig was no modernist, unless internationalist humanism is modern, yet he understood, befriended and moved among modernists. Already as a schoolboy he and his school-fellows shared a passionate interest in modernist art and thought which Zweig, almost alone amongst them, retained throughout his life. He knew everyone, and entertained them at his home in Salzburg. He was qualified to judge.

Quite why Freud was so significant he does not and probably could not explain. He simply emphasises Freud's tendency to call a spade a spade, speaking his mind without fear or favour, and arguing his corner all the more intransigently when the truth, as Freud saw it, was attacked. And Zweig's intuition of Freud's greatness was surely correct. Without setting out here the arguments for this point of view, I will observe that for all that Freud may have got wrong, he got one thing right: whereas psychoanalysis has sometimes appeared, particularly in USA, to promise the perfectability of humankind, Freud told Zweig that he was unsurprised by the outbreak of brutality: culture could not dominate our drives, nor had our elemental urge to destruction been eradicated.

Zweig concludes his picture of Freud by praising him for, nearing the end, bravely working--writing--in the face of suffering; and finally, inviting his doctor to ease his passing, a passage doubtless written shortly before Zweig with his second wife also took their leave of this life. The glory of freedom which nourished Zweig, whose presence or absence he said he could sense, and of borderless travel within Europe which Zweig indicates was a key practical aspect of that freedom, had for Zweig, as for so many of us, departed. May we be spared the more extreme manifestations of hate, and of its sibling, the restriction of freedom in speaking and publishing, under which Zweig and many others in his time suffered.