Reading The Tin Drum in German, as a non-native speaker, is exhausting. By page 100 I was among those casually posting online that the language, for a student of German, is a little difficult by post-war standards: not too challenging. On completion of the 493 closely printed pages, I was finding it shatteringly difficult. Which is odd, because when plouging through books in dead and living foreign languages, normally one becomes acclimatized to the style, and exercising one's Latin or French reading skills on that particular writer grows easier. I think the emotional difficulty of the book, which unfolds as pre-war, wartime and post-war horror follows horror, interacts with the challenge of understanding the words on the page. I also suggest that there is a subtle lesson for language learners in the difficulties created by Grass's dead-pan presentation of things which should be felt.

I would call the book "post-modern". Whatever post-modernism really means, by modernism I mean the inward turn which followed psychoanalysis, Nietzsche's death of God, stream of consciousness fiction, expressionist painting and poetry: art and thought which places at the centre of its world not a romantic self, but a self which emerges from an all-too-human, incoherent, chaotic, kaleidoscope of experiences, thoughts and feelings. Of course the pundits will stop reading there because they know what "modernism" really means, and will perhaps favour me with a correction before choking on their cornflakes over my conception of "post-modernism". The Tin Drum is often cited as "magic realism". In calling it "post-modern" I mean that the terrible events it depicts do not even build or disturb a coherent sense of self because they fall beyond the grasp of the shattered ego.

The main character in The Tin Drum recounts extraordinary violence, the Nazi time, chaotic family life, and many deaths in such a matter-of-fact way that they do not seem to have touched him. And yet he goes through life beating out his experience on a tin drum, or rather a series of tin drums because his beats the drums to destruction. From time to sings with the specific and only objective of shattering glass with his voice, a skill he was proud of. That is surely an expression of distress, since it hard to hear the glass-shattering 'singing' as musical, as well as distressing for the home owners whose glass he shatters just because he can, and for the shopkeepers whose windows he shatters to facilitate burgling them.

Oskar decides to stop growing at the age of three, so he becomes a hunchbank dwarf. There are several of those in German literature--Canetti's only novel has a Jewish hunchback midget Fischer, with the oddly Germanic forename Siegfried, and there is symbolism in the homunculus figure. What is odder is that having stopped developping at the age of three, the narrator has never lost the toddler habit of flipping between the first person "I" and the third person "Oskar" in describing his actions. So his lack of grasp of the tragedy around him, which may be compared with Camus' L'Étranger, is not entirely that of an adult, not of an ego too shattered by horror to react: it that of an ego which in the face of horror has chosen not to develop the capacity to engage as a fully-fledged individuum, with the pain which that entails. Once the sense of "I" is enduringly there, young chldren tend to drop the habit of referring to themselves by name, in the third person. Oskar never does.

Emotion is central to learning language. Language teachers often caution that foreign learners rarely grasp the import of swearwords: witness the casual use of the F word on German TV. Dialect speakers. Terms of intimacy have their effect in an exotic foreign language, or in a homely dialect but do not work in formal language. Perhaps grammar too touches the emotions: researchers whose favourite toy is a brain scanner can identify a pulse in the brain, presumably correlated with a sense of mild recoil, when a native speaker of a language is made to hear a grammatical error.

Although The Tin Drum is skillfully written, and one could stiffly describe Grass's German as 'rewarding', the constant recounting of horror without emotion in itself--aside from whatever difficulties the German may present--made the German difficult for me. One longs for gorgeous prose, or better, resonant verse which wise teachers both of native and foreign languages used to make students learn by heart, a wisdom which is largely but not wholly lost to the teaching profession. Even dogerrel mnemonics help the memory because even bad verse touches, if lightly, an emotional facutly in the learner.

And so in The Tin Drum there is no verse, and no music with an emotional effect on the narrator. Oskar's jazz band, who play in a bar which serves neither food nor drink but distributes onions to allow the guests to have a good weep, play nothing he enjoys, or the reader is made to feel is really musical. Not a line of verse, nor music with emotion, until the very end of the last page. It is a reworking of a children's folksong:

Schwarz war die Köchin hinter mir immer schon...Ist die schwarze Köchin da? Ja--Ja--Ja! (The cook behind me was always black... Is the black cook here? Yes, yes, yes!). Finally a song with some emotion. It is the emotion of being constantly pursued by dread.

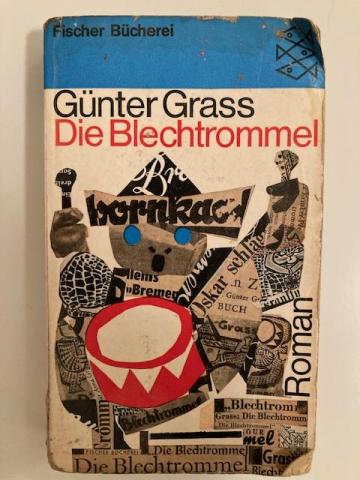

One can say Die Blechtrommel is a great book, worthy Grass's Nobel Prize. It is full of fascism, racial division, the partition of Germany, or religion presented as nugatory, and of horrible deaths as pantomime. And near the end there are policemen (not named as such) who out of pure duty are set on fulfilling and executing, five years after World War II, an order issued to them in 1939 to hunt down and shoot a short-sighted postman. Because that is their duty.

Was horror and cruelty the inevitable result of the hope-filled, tradition-dismantling modernist turn? In my use 'post-modernism', was the dumb and detached relation of the shattered or unformed ego to that horror, which The Tin Drum was far from alone is exploting for art, also inevitable? The answer is in effect a question in counter-factual history. Having just heard on the podcast It's All Greek (and Latin) to me some illuminating comments on the phrase Carpe Diem, it occurs to me not that is difficult to 'pluck the day' (as was suggested in the podcast). For Oskar, the main character in The Tin Drum, it was impossibleto enjoy the day: he simply did not have the equipment to do so.

There is a lot more to the novel than that. It is one of those novels which one does--at any rate I did not--recognize as great literature until the reading thereof is complete. I am glad I read it, glad it is over, and cannot imagine putting myself through it again, experiencing terrible events through eyes of a narrator who is by choice and necessity, both stunted physically, which is almost endearing, an emotional cripple, which is not.